Portrait of Antiquity

Crimea was (and still is) uniquely studded with fallen slabs, old foundations, ancient walls, gravestones, and mounds of earth that have grown incrementally over the years to cover the bones of past lives. On my first visit to Sevastopol a friend explained that every good rain dislodged chards of pottery, the occasional coin, and other sundry treasures. And sure enough, when we went trekking in the mountains above Laspi later that week - keeping a sharp eye out for wild boar - I found three small bits of pottery, the edges worn smooth but the greens and blues of their surfaces still vivid. My friend chuckled and dismissed them as insignificant - the pieces dated to the fourteenth or maybe fifteenth century, after all - but I savored the extraordinary feeling of that small weight in my palm, sun-warm and heavy with historical memory.

In 1837 the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg published a remarkable study On the Antiquities of the Southern Coast of Crimea and the Tavridan Mountains. The book's author, Peter Keppen, spent 5 years living in Crimea while serving as assistant to the chief of silk production (shelkovodstvo). During that time he traveled almost obsessively, collecting material for his geographical and archaeological projects.

In the dedication (addressed, of course, to Tsar Nicholas I), Keppen describes Crimea as "the most charming of all the countries prospering" under Romanov rule. His book lovingly documents the location, history, and status of inscribed stones, marble columns, churches, and tombstones, but the bulk of material details defensive towers and walls. Keppen saw Crimea - in antiquity - as a territory divided between a savage, predatory north and a luxuriously beautiful south hemmed in by the Tauride (or Tavridan) mountains on one side and the Black Sea on the other. The fortified line that separated one from the other was, to him, one of the two organizing features of Crimean space (or of its antique space anyway).

The second feature was sedimentation. Keppen was acutely aware of the way in which the passage of time imprinted itself on the landscape. At one point he describes finding the remains of an ancient fortification with thick walls of "wild stone" on the heights of Ayudag. "And is it surprising?" Keppen asks. "One must remember that this place has not been inhabited since 1475. And since then the spring sun has warmed the mountain tops and new growth has sprung from the depths of the earth no fewer than 360 times. 360 times over autumn storms have torn the leaves from trees and ripped the grasses, each year creating a new layer to cover any traces of human existence!"(170)

Keppen would tell you that to see Crimea, one had to dig.

This collection contains all of the sites (though not all of the individual stones!) discussed in On the Antiquities of the Southern Coast. It includes 4 mausoleums, 9 Greek churches, and 58 fortifications. Each and every one was a ruin even before Keppen laid eyes on it.

Related gallery: Uvarov's Antiquities

Related narrations: Among the Ruins & A Monumental Inscription

Related source map: Keppen's Antiquities

Beshui (Beshue, Beshev)

Ruins of a Greek church

Stilia

Ruins of a Greek church. Keppen found an inscription on the slab above the door with far more recent provenance than the church itself. The Russian translation of the Greek runs as follows: Gervasij Ieromonakh Sumely, puteshestvie 1754; 176.; 1765.…

Ulusala

Ruins of a Greek church

Biasala

Ruins of a Greek church. The only example of an angular (rather than semispherical) altar identified by Keppen.

Buyuk Lambat

Ruins of a Greek church

Ulu Uzen

Ruins of a Greek church

Ai-Vasil

Ruins of a Greek church

Foot of Kilse Kaya and Aiazma Kaya

Ruins of a Greek church

Kopsele

Ruins of a Greek church

Bakhchisaray

Site of a durbe (Tatar mausoleum)

Salaçık

Site of a durbe (Tatar mausoleum)

Chufut-Kale

Site of a durbe (Tatar mausoleum)

Eski Iurt

Site of a durbe (Tatar mausoleum)

Otuz

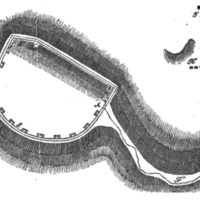

The Otuz fortification is situated on a substantial hill three-quarters of an hour from the village of Otuz, down near the sea. Its significance lies in the fact that it is the most easterly of the fortifications on the coastal side of the mountains.…

Tash Kapu / Khabakh Tash

Located one and one-quarter hours travel from Otuz on the road to Staryi Krym. On Mukhin's map, Khabakh Tash is called "ruins of Otuz".

Eltigen

10 minutes north of the village of Kozy along the Otuz road. The site includes the remains of ancient limestone walls 18 vershki (31.5 inches) thick and nearly 2 sazhens high, and a Greek church.

Tash Khabakh

"Stone gate". The site is located on the way from Kozy to Taraktash; on the right, and about a verst from the road.

Khaplaryn Bogaz

A gorge on the road leading from Taraktash to Kutly in the Karagach forest (about an hour from Kutly, less than two hours from Suuk-Su, 6 or 7 versts from Taraktash and 10 versts from the Karagach forest). When it comes down to it, Keppen isn't quite…

Sudak

Keppen includes a suitably long discussion of the history of Sudak, which extends back to the 8th century CE. Along the way he mentions that while there were hundreds of churches in the second half of the sixteenth century, his study of the area…

Kaskule and Kalepartash

Keppen found no antiquities at Kaskule or Kalepartash despite the promise of their names ("kule" means tower and "kale" means fortification). He also notes that on November 25, 1834, he spent half a day slogging through miserable weather from Kutly…

Choban Kale

Ruins right along the sea near Arpat (halfway between Kapsikhor and Uskiut).

Demir Khapu / Tash Duvar

In the yaila northwest of Arpat, Demir Khapu is a two-hour walk from Uskiut. Nearly two hours further along the road one comes to Tash Duvar and the remains of a long defensive wall. Tash Duvar is owned by Murat Mirza, son of Megmetsha Argin.

Aksak Temir

Remains of an ancient wall some 7 verts in length.

Gurliuk

In the area of the Greek village of Enisala, along the post road, the remains of a wall are still visible. Locals from the village of Chavke claim that the wall was built by someone named Aksan-Temir Bagatyr.(143-144)

Tash Khabakh

Remains of a stone wall.

Demir Khapu

Nearby at Eklis Burun there is a stone church and wall. They would have been able to communicate with Demir Khapu using signal lights. Keppen claims to have detected traces of a road through the forest and cliff walls. He also notes that in the deep…

Bitlan / Kastro

Located at the western end of Kuchuk Uzen.

Alushta

The fort at Alushta dates to the 6th century. Keppen's notes are particularly conversational. He takes it upon himself to offer an explanation of why Sumarokov claims Alushta was called Furion and references Pallas as well, asking "where did he get…

Demir Khapu

The old coastal road from Alushta to Kuchuk Lambat is 9 versts and 400 sazhens. The halfway point is marked by the Demir Khapu (iron gate). From there the remains of a wall leading down to the shore are visible. Demir Khapu and Kastel Mountain both…

Ay Todor

The walls of a fortification are still visible, and Keppen identifies them as defensive. Near the mountain top Keppen traces out the remains of a rectangular structure 13 by 9 paces with walls around it - likely a church. There is another church of…

Lambat

Some 2,000 inhabitants now.

Vigla / Demir Khapu

Vigla is an urochishche near Partenit. Demir Khapu is a narrow place marked by a fountain between the mountain and forest. Demir Khapu to Gurzuf takes 3 hours.

Ayudag (Buyuk Kastel)

On the heights of Ayudag are the remains of an ancient fortification with thick walls of "wild stone" but little else. "And is it surprising?" Keppen asks. "One must remember that this place has not been inhabited since 1475. And from that time no…

Gelin-Kaya

Above Kiziltash, on the coastal side, Keppen located the walls indicating the fortification strategically placed here, with sightlines extending to Ayudag, Gurzuf, Gurbte-dere Bogaz (whence the main road into the mountains, via Kuush, begins). A…

Vigla / Gramata

Vigla-Bair is at the eastern boundary of Gurzuf above Kalitsa-Sheshma, the water source 2 versts from Gurzuf, and below the forest called Shiurmen. Gramata is the site of an inscribed stone. It is in the yaila, 3 hours from Gurzuf and 7 versts from…

Gurzuf

Another 6th century site. Keppen includes an excerpt from Pallas, cites Greviev, Barbaro, Vitsen, Peysonnel, Thunman. He adds little commentary of his own.(175-177)

Ruskofil Kale

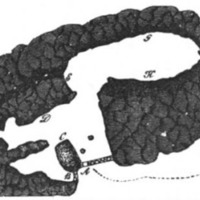

Keppen's Tatar companions told him that this was the site (on the Nikita mys) of a monastery. Keppen approached from the state garden to the east and immediately saw the remains of a wall and further down the cave known as Khale Khoba (Kale Koba), 10…

Palikaster

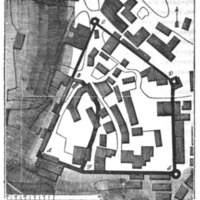

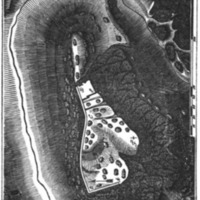

To the right of the main road from Nikita to Magarach. Standing at point A (see illustration), to the southwest are visible Uchanskuskoe, Yalta, Orianda, and Ay-Todor. (179-181)

Yalta

At Marsanda the remains of a church are visible down near the sea, but Keppen is unsure whether this site was fortified. The church on the cape of St. John was behind walls.

Uchansu Isar

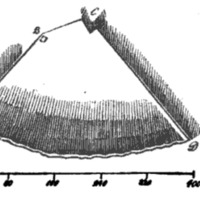

A spot for those who seek out "spectacles of nature." In this case, the spectacle is a waterfall careening from the heights above the fortification. (Uchan-su means "flying water" in Tatar.) A mere 40 minute trip from Yalta brings the visitor to the…

Orianda

The earliest cartographic attestation of Orianda, according to Keppen, is in the 1480 "atlas of Beninkaza of Ancona" [here he is referring to the portolan chart of the Black Sea by the famous cartographer Grazioso Benincasa], which Count Ivan (Jan)…

Cape Ay Todor

One of the trio of capes that mark the shift in topography from the southwesterly line to a westerly line along the coast to Balaklava. Anyone stationed here could see Ruskofil Kale, Palikaster, Yalta, Uchansu-Isar, and Orianda. Only the foundations…

Gaspra Isar

Northwest of the cape of Ay Todor. This fortification is "the work of nature": a glade 40 feet by 8 feet almost completely enclosed by walls of rock.(194)

Alupka Isar

The trip from Alupka to the fortification takes an hour and a half. There among the towering pines are the remains of various buildings.(196-198)